26. Libraries and Modules

A library is a collection of code for functions and classes. Often, these libraries are written by someone else and brought into the project so that the programmer does not have to „reinvent the wheel.“ In Python the term used to describe a library of code is module.

By using import arcade and import random, the programs created so far have

already used modules. A library can be made up of multiple modules that can be

imported. Often a library only has one module, so these words can sometimes be

used interchangeably.

Modules are often organized into groups of similar functionality. In this class

programs have already used functions from the math module, the random module,

and the arcade library. Modules can be organized so that individual modules

contain other modules. For example, the arcade module contains submodules for

arcade.key, and arcade.color.

Modules are not loaded unless the program asks them to. This saves time and computer memory. This chapter shows how to create a module, and how to import and use that module.

26.1. Why Create a Library?

There are three major reasons for a programmer to create his or her own libraries:

It breaks the code into smaller, easier to use parts.

It allows multiple people to work on a program at the same time.

The code written can be easily shared with other programmers.

Some of the programs already created in this book have started to get rather long. By separating a large program into several smaller programs, it is easier to manage the code. For example, in the prior chapter’s sprite example, a programmer could move the sprite class into a separate file. In a complex program, each sprite might be contained in its own file.

If multiple programmers work on the same project, it is nearly impossible to do so if all the code is in one file. However, by breaking the program into multiple pieces, it becomes easier. One programmer could work on developing an „Orc“ sprite class. Another programmer could work on the „Goblin“ sprite class. Since the sprites are in separate files, the programmers do not run into conflict.

Modern programmers rarely build programs from scratch. Often programs are built from parts of other programs that share the same functionality. If one programmer creates code that can handle a mortgage application form, that code will ideally go into a library. Then any other program that needs to manage a mortgage application form at that bank can call on that library.

26.2. Creating Your Own Module/Library File

Video: Libraries

In this example we will break apart a short program into multiple files. Here

we have a function in a file named test.py, and a call to that function:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | # Foo function def foo(): print("foo!") def main(): # Foo call foo() main() |

Yes, this program is not too long to be in one file. But if both the function and the main program code were long, it would be different. If we had several functions, each 100 lines long, it would be time consuming to manage that large of a file. But for this example we will keep the code short for clarity.

We can move the foo function out of this file. Then this file would be left

with only the main program code. (In this example there is no reason to

separate them, aside from learning how to do so.)

To do this, create a new file and copy the foo function into it. Save the

new file with the name my_functions.py. The file must be saved to the same

directory as test.py.

1 2 3 | # Foo function def foo(): print("foo!") |

1 2 3 4 5 | def main(): # Foo call that doesn't work foo() main() |

Unfortunately it isn’t as simple as this. The file test.py does not know to

go and look at the my_functions.py file and import it. We have to add the

command to import it:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | # Import the my_functions.py file import my_functions def main(): # Foo call that still doesn't work foo() main() |

That still doesn’t work. What are we missing? Just like when we import arcade, we have to put the package name in front of the function. Like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | # Import the my_functions.py file import my_functions def main(): # Foo call that does work my_functions.foo() main() |

This works because my_functions. is prepended to the function call.

26.3. Namespace

Video: Namespace

A program might have two library files that need to be used. What if the libraries had functions that were named the same? What if there were two functions named print_report, one that printed grades, and one that printed an account statement? For instance:

1 2 | def print_report(): print("Student Grade Report:" ) |

1 2 | def print_report(): print("Financial Report:" ) |

How do you get a program to specify which function to call? Well, that is pretty easy. You specify the namespace. The namespace is the work that appears before the function name in the code below:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | import student_functions import financial_functions def main(): student_functions.print_report() financial_functions.print_report() main() |

So now we can see why this might be needed. But what if you don’t have name

collisions? Typing in a namespace each and every time can be tiresome. You

can get around this by importing the library into the local namespace. The

local namespace is a list of functions, variables, and classes that you

don’t have to prepend with a namespace. Going back to the foo example,

let’s remove the original import and replace it with a new type of import:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | # import foo from my_functions import * def main(): foo() main() |

This works even without my_functions. prepended to the function call. The

asterisk is a wildcard that will import all functions from my_functions.

A programmer could import individual ones if desired by specifying the

function name.

26.4. Third Party Libraries

When working with Python, it is possible to use many libraries that are built into Python. Take a look at all the libraries that are available here:

http://docs.python.org/3/py-modindex.html

It is possible to download and install other libraries. There are libraries that work with the web, complex numbers, databases, and more.

Arcade: The library that this book uses to create games. https://api.arcade.academy

Pygame: Another library used to create games, and the inspiration behind the creation of the Arcade library. http://www.pygame.org/docs/

Pymunk: A great library for running 2D physics. Also works with Arcade, see these examples http://www.pymunk.org/

wxPython: Create GUI programs, with windows, menus, and more. http://www.wxpython.org/

pydot: Generate complex directed and non-directed graphs http://code.google.com/p/pydot/

NumPy: Sophisticated library for working with matrices. http://numpy.org/

Pandas: A library for data analysis. https://pandas.pydata.org/

Pillow: Work with images. https://pillow.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

Pyglet: Another graphics library. Arcade uses this library. http://pyglet.org/

You can do analysis and create your own interactive notebook using Jupyter:

Jupyter: http://jupyter.org/

Some libraries we give examples of in this chapter:

OpenPyXL: A library for reading and writing Excel files. https://openpyxl.readthedocs.io/en/stable/

Beautiful Soup: Grab data off websites, and create your own web bots. https://www.crummy.com/software/BeautifulSoup/

MatPlotLib: Plot data automatically: https://matplotlib.org/

A wonderful list of Python libraries and links to installers for them is available here:

You can search up some top packages/libraries and stand alone projects to get an idea of what you can do. There are many articles like Top 15 Python Libraries for Data Science in 2017.

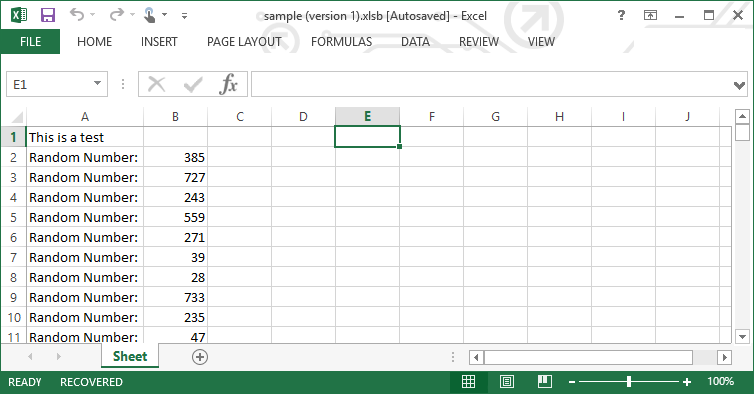

26.4.1. Examples: OpenPyXL Library

This example uses a library called OpenPyXL to write an Excel file. It is also

easy to read from an Excel file.

You can install OpenPyXL from the Windows command prompt by typing

pip install openpyxl.

If you are on the Mac or a Linux machine, you can type sudo pip3 install openpyxl.

Bemerkung

When starting the command prompt, you might need to right-click on it and select „Run as administrator“ if you get permission errors when installing. And if you are working on a lab computer, you might not have permission to install libraries.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 | """ Example using OpenPyXL to create an Excel worksheet """ from openpyxl import Workbook import random # Create an Excel workbook work_book = Workbook() # Grab the active worksheet work_sheet = work_book.active # Data can be assigned directly to cells work_sheet['A1'] = "This is a test" # Rows can also be appended for i in range(200): work_sheet.append(["Random Number:", random.randrange(1000)]) # Save the file work_book.save("sample.xlsx") |

The output of this program is an Excel file:

26.4.2. Examples: Beautiful Soup Library

This example grabs information off a web page.

You can install Beautiful Soup from the Windows command prompt by typing

pip install bs4. If you are on the Mac or a Linux machine, you can type

sudo pip3 install bs4.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | """ Example showing how to read in from a web page """ from bs4 import BeautifulSoup import urllib.request # Read in the web page url_address = "http://simpson.edu" page = urllib.request.urlopen(url_address) # Parse the web page soup = BeautifulSoup(page.read(), "html.parser") # Get a list of level 1 headings in the page headings = soup.findAll("h1") # Loop through each row for heading in headings: print(heading.text) |

26.4.3. Examples: Matplotlib Library

Here is an example of what you can do with the third party library „Matplotlib.“

You can install Matplotlib from the Windows command prompt by typing

pip install matplotlib. If you are on the Mac or a Linux machine, you can

type pip3 install matplotlib.

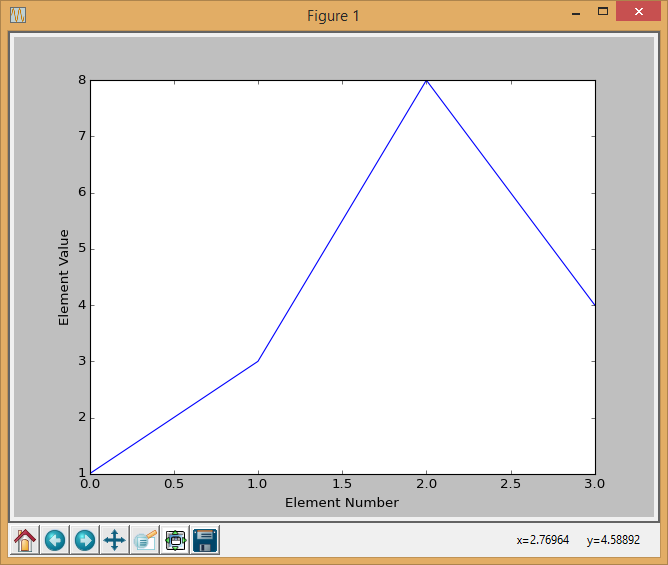

26.4.3.1. Example 1: Simple Plot

To start with, here is the code to create a simple line chart with four values:

Simple Line Graph

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | """ Line chart with four values. The x-axis defaults to start at zero. """ import matplotlib.pyplot as plt y = [1, 3, 8, 4] plt.plot(y) plt.ylabel('Element Value') plt.xlabel('Element Number') plt.show() |

Note that you can zoom in, pan, and save the graph. You can even save the graph in vector formats like ps and svg that import into documents without loss of quality like raster graphics would have.

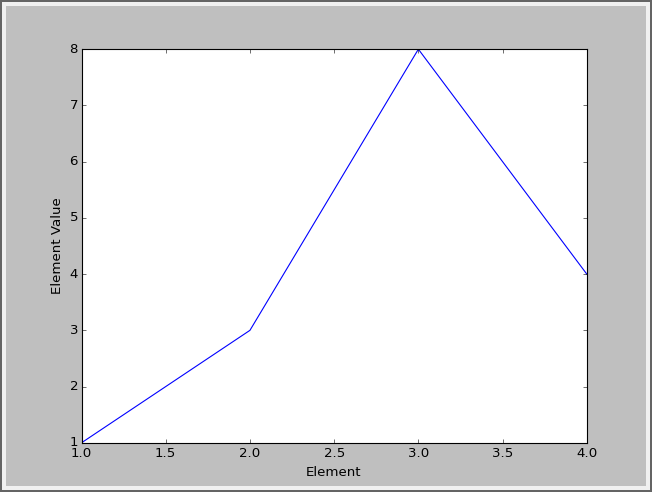

26.4.3.2. Example 2: Specify x Values

The x value for Example 1, defaults to start at zero. You can change this default and specify your own x values to go with the y values. See Example 2 below.

Specifying the x values

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | """ Line chart with four values. The x-axis values are specified as well. """ import matplotlib.pyplot as plt x = [1, 2, 3, 4] y = [1, 3, 8, 4] plt.plot(x, y) plt.ylabel('Element Value') plt.xlabel('Element') plt.show() |

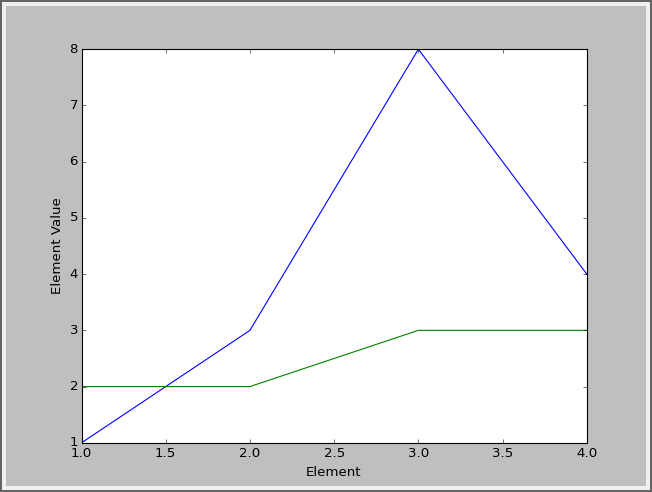

26.4.3.3. Example 3: Add A Second Data Series

It is trivial to add another data series to the graph.

Graphing two data series

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | """ This example shows graphing two different series on the same graph. """ import matplotlib.pyplot as plt x = [1, 2, 3, 4] y1 = [1, 3, 8, 4] y2 = [2, 2, 3, 3] plt.plot(x, y1) plt.plot(x, y2) plt.ylabel('Element Value') plt.xlabel('Element') plt.show() |

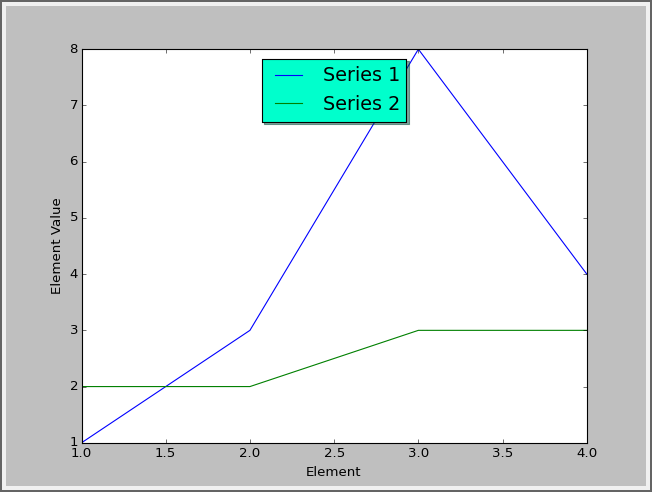

26.4.3.4. Example 4: Add A Legend

You can add a legend to the graph:

Adding a legend

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | import matplotlib.pyplot as plt x = [1, 2, 3, 4] y1 = [1, 3, 8, 4] y2 = [2, 2, 3, 3] plt.plot(x, y1, label = "Series 1") plt.plot(x, y2, label = "Series 2") legend = plt.legend(loc='upper center', shadow=True, fontsize='x-large') legend.get_frame().set_facecolor('#00FFCC') plt.ylabel('Element Value') plt.xlabel('Element') plt.show() |

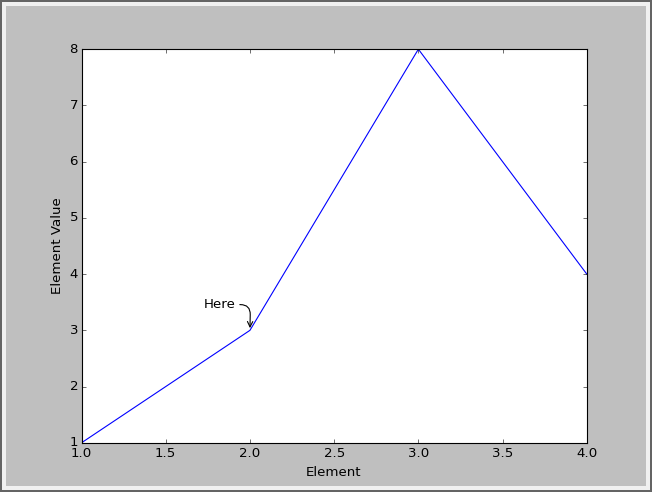

26.4.3.5. Example 5: Add Annotations

You can add annotations to a graph:

Adding annotations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 | """ Annotating a graph """ import matplotlib.pyplot as plt x = [1, 2, 3, 4] y = [1, 3, 8, 4] plt.annotate('Here', xy = (2, 3), xycoords = 'data', xytext = (-40, 20), textcoords = 'offset points', arrowprops = dict(arrowstyle="->", connectionstyle="arc,angleA=0,armA=30,rad=10"), ) plt.plot(x, y) plt.ylabel('Element Value') plt.xlabel('Element') plt.show() |

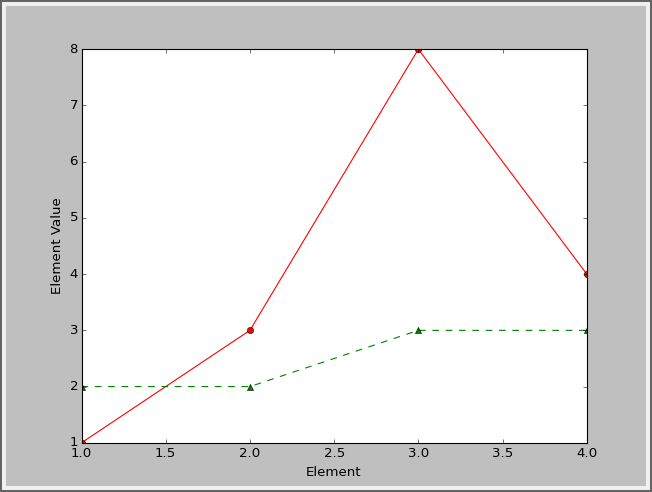

26.4.3.6. Example 6: Change Line Styles

Don’t like the default lines styles for the graph? That can be changed by adding a third parameter to the plot command.

Specifying the line style

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 | """ This shows how to set line style and markers. """ import matplotlib.pyplot as plt x = [1, 2, 3, 4] y1 = [1, 3, 8, 4] y2 = [2, 2, 3, 3] # First character: Line style # One of '-', '--', '-.', ':', 'None', ' ', " # Second character: color # http://matplotlib.org/1.4.2/api/colors_api.html # Third character: marker shape # http://matplotlib.org/1.4.2/api/markers_api.html plt.plot(x, y1, '-ro') plt.plot(x, y2, '--g^') plt.ylabel('Element Value') plt.xlabel('Element') plt.show() |

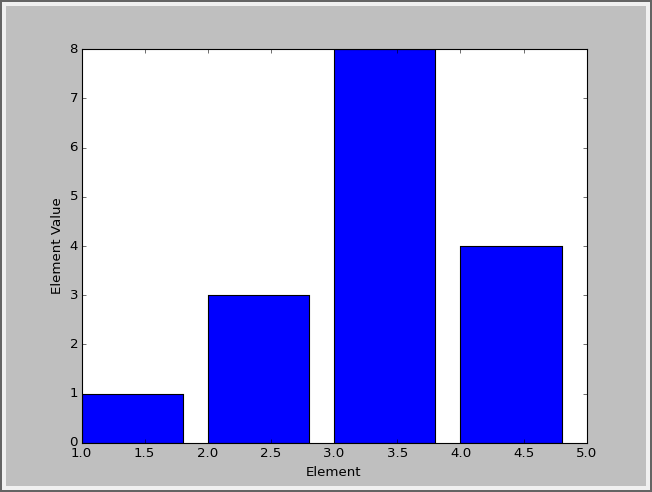

26.4.3.7. Example 7: Bar Chart

A bar chart is as easy as changing plot to bar.

Bar chart

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | """ How to do a bar chart. """ import matplotlib.pyplot as plt x = [1, 2, 3, 4] y = [1, 3, 8, 4] plt.bar(x, y) plt.ylabel('Element Value') plt.xlabel('Element') plt.show() |

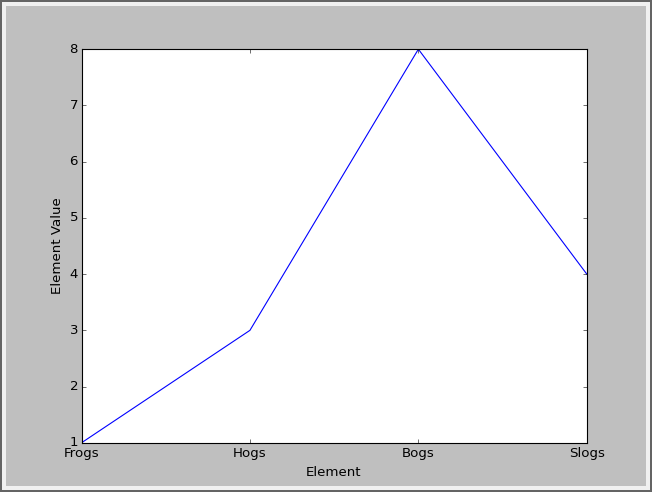

26.4.3.8. Example 8: Axis Labels

You can add labels to axis values.

X-axis labels

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | """ How to add x axis value labels. """ import matplotlib.pyplot as plt x = [1, 2, 3, 4] y = [1, 3, 8, 4] plt.plot(x, y) labels = ['Frogs', 'Hogs', 'Bogs', 'Slogs'] plt.xticks(x, labels) plt.ylabel('Element Value') plt.xlabel('Element') plt.show() |

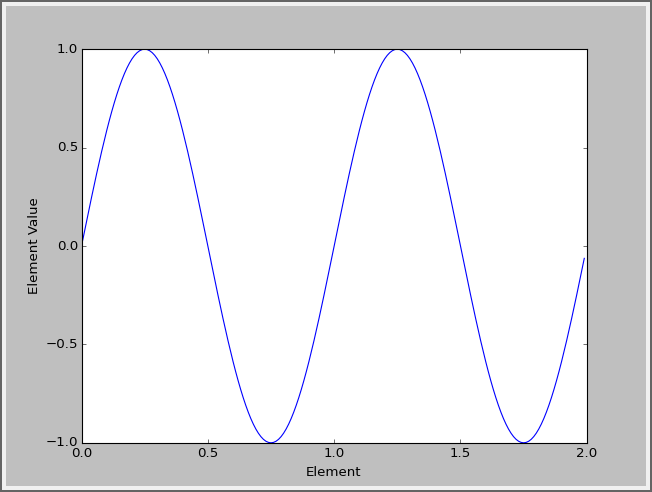

26.4.3.9. Example 9: Graph Functions

You can graph functions as well. This uses a different package called numpy to graph a sine function.

Graphing a sine function

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | """ Using the numpy package to graph a function over a range of values. """ import numpy import matplotlib.pyplot as plt x = numpy.arange(0.0, 2.0, 0.001) y = numpy.sin(2 * numpy.pi * x) plt.plot(x, y) plt.ylabel('Element Value') plt.xlabel('Element') plt.show() |

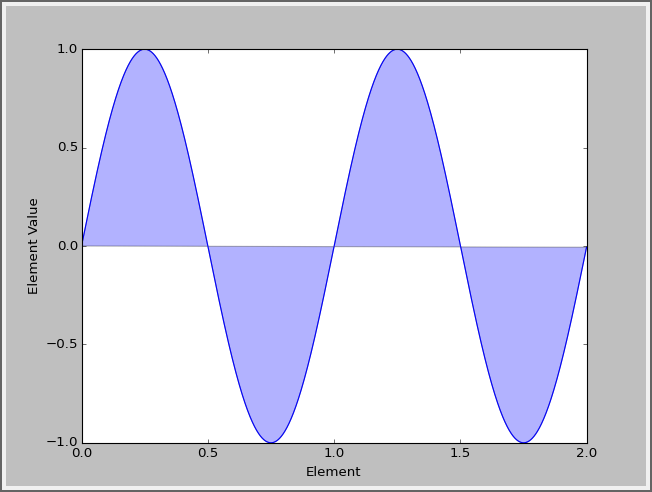

26.4.3.10. Example 10: Graph Functions With Fill

You can fill in a graph if you like.

Filling in a graph

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | """ Using 'fill' to fill in a graph """ import numpy import matplotlib.pyplot as plt x = numpy.arange(0.0, 2.0, 0.001) y = numpy.sin(2 * numpy.pi * x) plt.plot(x, y) # 'b' means blue. 'alpha' is the transparency. plt.fill(x, y, 'b', alpha=0.3) plt.ylabel('Element Value') plt.xlabel('Element') plt.show() |

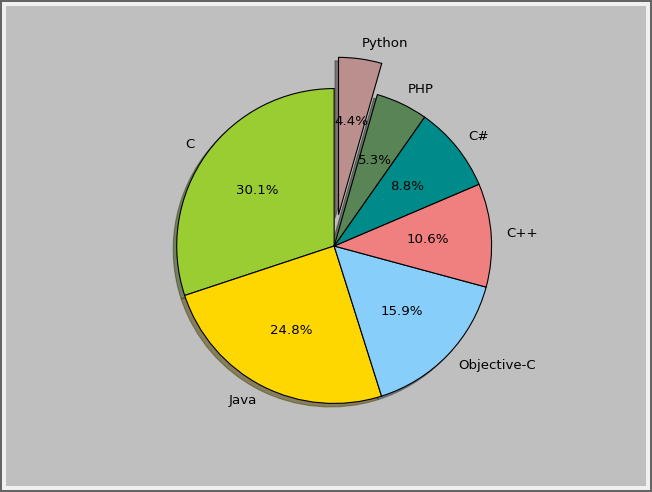

26.4.3.11. Example 11: Pie Chart

Create a pie chart.

Pie chart

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 | """ Create a pie chart """ import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # Labels for the pie chart labels = ['C', 'Java', 'Objective-C', 'C++', 'C#', 'PHP', 'Python'] # Sizes for each label. We use this to make a percent sizes = [17, 14, 9, 6, 5, 3, 2.5] # For list of colors, see: # https://matplotlib.org/examples/color/named_colors.html colors = ['yellowgreen', 'gold', 'lightskyblue', 'lightcoral', 'darkcyan', 'aquamarine', 'rosybrown'] # How far out to pull a slice. Normally zero. explode = (0, 0.0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.2) # Set aspect ratio to be equal so that pie is drawn as a circle. plt.axis('equal') # Finally, plot the chart plt.pie(sizes, explode=explode, labels=labels, colors=colors, autopct='%1.1f%%', shadow=True, startangle=90) plt.show() |

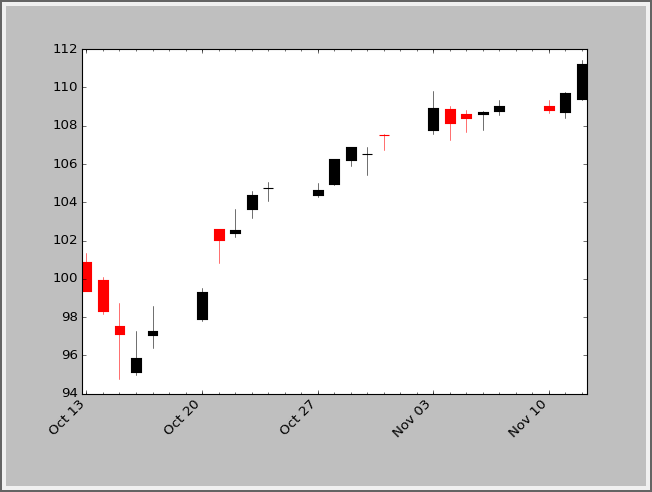

26.4.3.12. Example 12: Candlestick Chart

You can do really fancy things, like pull stock data from the web and create a candlestick graph for Apple Computer:

Candlestick chart

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 | """ Create a candlestick chart for a stock """ import matplotlib.pyplot as plt from matplotlib.dates import DateFormatter, WeekdayLocator,\ DayLocator, MONDAY from matplotlib.finance import quotes_historical_yahoo_ohlc, candlestick_ohlc # Grab the stock data between these dates date1 = (2014, 10, 13) date2 = (2014, 11, 13) # Go to the web and pull the stock info quotes = quotes_historical_yahoo_ohlc('AAPL', date1, date2) if len(quotes) == 0: raise SystemExit # Set up the graph fig, ax = plt.subplots() fig.subplots_adjust(bottom=0.2) # Major ticks on Mondays mondays = WeekdayLocator(MONDAY) ax.xaxis.set_major_locator(mondays) # Minor ticks on all days alldays = DayLocator() ax.xaxis.set_minor_locator(alldays) # Format the days weekFormatter = DateFormatter('%b %d') # e.g., Jan 12 ax.xaxis.set_major_formatter(weekFormatter) ax.xaxis_date() candlestick_ohlc(ax, quotes, width=0.6) ax.autoscale_view() plt.setp(plt.gca().get_xticklabels(), rotation=45, horizontalalignment='right') plt.show() |

There are many more things that can be done with matplotlib. Take a look at the thumbnail gallery: